3 Analysis of the status after discharge from juvenile training schools

(1) Residential status, etc.

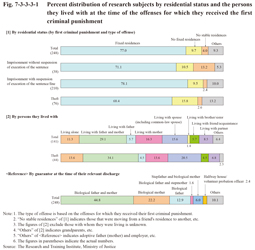

Fig. 7-3-3-3-1 shows the residential status and who they were living with at the time of the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment (the offense with the heaviest statutory penalty was selected in cases where multiple offenses were involved, and the offense that caused the greatest damage was selected in cases where more than one offense of the same type was involved; hereinafter the same in this subsection) of all the research subjects that received criminal punishment (248 persons) and those that received criminal punishment for theft. Of all the research subjects of concern 77.0% had fixed residences, 9.7% did not have fixed residences, and 4.0% did not have stable residences, and thus those with unstable residential statuses totaled 13.7%. Of those that received imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence the proportion of those with unstable residential statuses was higher than that of those that received other types of criminal punishment. With those that received their first criminal punishment for theft the residential status of nearly 20% of them was unstable (15.8% without fixed residences and 2.6% without stable residences). The percentage was high when compared with all the research subjects of concern.

Of 141 research subjects with residences whose status on whom they lived with could be identified, examining the percent distribution of the persons with whom they lived revealed that those who lived with their father and mother (including cases where the research subjects lived with either one; hereinafter the same) accounted for 51.1%, those who lived with a spouse (including common-law spouse) 15.6%, those who lived with a friend/acquaintance 5.7%, and those who lived alone 11.3%. This percent distribution is significantly different from that of guarantors at the time of their relevant discharge given in the figure as a reference (the same with those that received their first criminal punishment for theft), thus indicating that many stopped living with their supervisors before committing the offenses for which they received their first criminal punishment.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-1 Percent distribution of research subjects by residential status and the persons they lived with at the time of the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment

Fig. 7-3-3-3-2 shows the percent distribution of those that did not have fixed/stable residences at the time of the offense by type of offense. Theft accounted for the largest proportion at 41.2% and property offenses including robbery and fraud 58.8%, and thus their unstable residential status was considered to be a particular factor that led them to property offenses (See Table 7-2-3-6 for percentage of new inmates that did not have fixed residences)

Fig. 7-3-3-3-2 Percent distribution of research subjects without fixed residences, etc. by type of offense

(2) Employment status

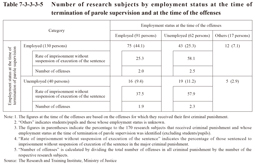

Fig. 7-3-3-3-3 shows the employment status at the time of the offenses for which they received their first criminal punishment by type of offense. Of all the research subjects of concern (248 persons) 52.4% were employed and 36.7% unemployed. The rate of unemployed persons (percentage of those unemployed to the total of those unemployed and those employed) of all the research subjects of concern was 41.2%, which was remarkably higher than that of juvenile training school parolees at the time of termination of their parole supervision (23.8% in 2010; See Fig. 7-2-4-6 [2]). That of those that received their first criminal punishment for Stimulants Control Act violations and theft was even higher at 52.9% and 46.2%, respectively.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-3 Employment status at the time of the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment

Fig. 7-3-3-3-4 shows the employment status of those belonging to the sexual offense type at the time they committed the sexual offense (the first sexual offense in cases where multiple sexual offenses were committed). Of the 16 research subjects belonging to the sexual offense type 11 were employed, two unemployed, and three their employment status unknown, and thus the rate of unemployment persons was remarkably low when compared to all the research subjects of concern. The relationship between employment status and sexual offenses is therefore considered weak.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-4 Employment status of research subjects belonging to the sexual offense type

Examining the reason for not working of those unemployed at the time of offenses for which they received their first criminal punishment (91 persons) revealed that (See Fig. 7-3-3-3-3 [2]) of 67 of them whose reason was identified, only a few had unavoidable reasons such as “could not find a job” or “illness/injury, etc.” Those with the reason of “laziness” or “unlawful/illegal income” accounted for over 40%. Those with the reason of “laziness” who committed theft accounted for 50%, followed by violent offenses and robbery, and those with the reason of “unlawful/illegal income” who committed theft and violent offenses accounted for the largest in number, followed by robbery, thus indicating that the majority of those with either reason committed these offenses. This then indicates a relationship between problems with their consciousness and capacity to be employed and theft/violent offenses/robbery.

In addition, 74.7% of those unemployed had ever employed at least once, and examining their reasons for leaving the job revealed that (See Fig. 7-3-3-3-3 [3]) those with reasons for which they were not responsible such as “poor business results of workplaces” (12 persons) and “illness/injury, etc.” (eight), and “move/changing jobs” (five) were relatively few in number, but those with reasons that relate to their attitudes or capacity such as “bad relationships with others” (26), “defaulted” (24), and “dissatisfied with wages/treatment” (24), etc. accounted for the majority, thus the problems of their attitudes, including motivation to work, etc., and their capacity, including patience and human relations skills, etc., are considered significant in maintaining employment.

Table 7-3-3-3-5 shows the research subjects that received criminal punishment by employment status at the time of termination of parole supervision after their relevant discharge (on parole) and at the time of the offenses for which they received their first criminal punishment (excluding those whose employment status at the time of termination of their parole supervision was unknown). With those employed at the time of termination of their parole supervision, those also employed at the time of the offense accounted for the majority (rate of unemployed persons of 36.4%), whereas with those unemployed at the time of termination of their parole supervision, those also unemployed at the time of the offense accounted for the majority (rate of unemployed persons of 54.3%). On the fact that problems with their attitudes and capacity reflected on their reasons for not working/leaving a job, their employment status at the time of termination of parole supervision is considered to be connected with their subsequent employment status and to also have affected their criminal punishment status (See Fig. 7-3-3-1-7). In addition, the number of those employed both at the time of termination of their parole supervision and at the time of the offenses was 75, which was less than half of those that received criminal punishment, thus revealing that only a small number of them continued being employed after discharge. Comparing the percent distribution by type of offense of those employed both at the time of termination of their parole supervision and at the time of the offenses and that of those unemployed on at either time of these occasions revealed that the proportion of theft and negligence in vehicle driving causing death or injury, etc. was large with the former and the proportion of violent offenses, including assault and injury, etc., and property offenses including theft, robbery, extortion, and fraud, etc. was large with the latter. In addition, the rate of imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence (percentage of imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence in the major criminal punishment) and the number of offenses (average number of offenses in all criminal punishment) were both low/small with those employed on both occasions but both high/large with those unemployed at the time of the offenses. This leads to the assumption that the level of employment affects the status with offenses.

Table 7-3-3-3-5 Number of research subjects by employment status at the time of termination of parole supervision and at the time of the offenses

(3) Problematic behavior, etc. after discharge

a. General status

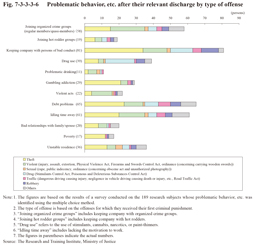

Fig. 7-3-3-3-6 shows the status with problematic behavior, etc. after their relevant discharge (limited to the period up to the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment) of those that received criminal punishment by type of offense in the first criminal punishment.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-6 Problematic behavior, etc. after their relevant discharge by type of offense

Of the 189 research subjects available for examination 10.1% did not have any problematic behavior, 15.3% had one type of problematic behavior, and 74.6% had two or more types of problematic behavior. Of the problematic behavior of concern, joining organized crime groups accounted for 30.7% (58 persons), joining hot rodder groups 10.1% (19), and keeping company with other persons of bad conduct 42.9% (81), and thus approximately 2/3 (125 persons (actual number), excluding those that fell into more than one category) had problems with their relationships with friends.

20.6% used drugs (not limited to drug use that was subject to criminal punishment) (of which 25 used stimulants, 14 paint-thinners, and nine cannabis, narcotics, or opium; including those that fell into more than one category) and 5.8% (11 persons) had drinking problems, and hence quite a few of them had a problem with substance abuse (problematic drinking/drug use).

In addition, 32.3% (61 persons) had the problem of idling time away (including lacking the motivation to work), 34.4% (65) debt problems, 15.3% (29) gambling addictions, and 9.0% (17) poverty, thus many had problems related to employment and financial instability.

Few had the types of problematic behavior, etc. of isolation, homelessness, or social withdrawal, etc.

As described above the common problematic behavior that the research subjects of concern had after their relevant discharge included associating with delinquent friends (refers to joining (including keeping company with) organized crime groups or hot rodder groups or keeping company with other persons of bad conduct; the number of persons excludes those that fell into more than one category; hereinafter the same in this section), unemployment, financial instability, drug dependency, etc.

Next, the various types of problematic behavior typically take place in combination, and hence their overlapping status is examined.

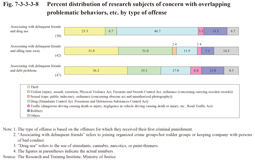

Fig. 7-3-3-3-7 shows the overlapping status of the most commonly observed problematic behavior of “associating with delinquent friends” with the other types.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-7 Status with overlapping problematic behaviors, etc.

76.9% (30 persons) of those involving drug use and 68.9% (42) of those idling time away also associated with delinquent friends, thus indicating the existence of a strong mutual relationship between drug use and associating with delinquent friends and between idling time away and associating with delinquent friends. 30.8% of those involving drug use and 19.7% of those idling time away involved both drug use and idling time away. This indicates that many of those with drug use problems also had the problem of idling time away.

69.0% (20 persons) of those with gambling addictions and 72.3% (47) of those with debt problems also associated with delinquent friends, and 47 in particular both associated with delinquent friends and had debt problems, accounting for 24.9% of the research subjects of concern, thus indicating that many of them had both these problems. In addition, those with both gambling addictions and debt problems accounted for 58.6% of those with gambling addictions and 26.2% of those with debt problems, thus indicating many of those with gambling problems also had debt problems.

Examining the relationship among associating with delinquent friends, problematic drinking and violent acts revealed that 77.3% of those involving violent acts also associated with delinquent friends, but the percentage of those with other overlapping problematic behaviors was small, thus indicating that these types of problematic behavior, in many cases, occur independently.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-8 shows the percent distribution by type of offense for which they received the first criminal punishment of those who both associated with delinquent friends and used drugs (30 persons), those who both associated with delinquent friends and idled time away (42), and those who both associated with delinquent friends and had debt problems (47), all of which were composed of a large number of the research subjects of concern who had overlapping problematic behaviors.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-8 Percent distribution of research subjects of concern with overlapping problematic behaviors, etc. by type of offense

With those who both associated with delinquent friends and used drugs the percentage of those that received criminal punishment for theft was not very high when compared with all the research subjects (See Table 7-3-2-3), but that for Stimulants Control Act violations or Poisonous and Deleterious Substances Control Act violations accounted for nearly half at 46.7%, and thus the percentage of those that received criminal punishment for drug offenses was higher than with those who used drugs but did not associate with delinquent friends (33.3%). Many of those with the problems of both associating with delinquent friends and idling time away received criminal punishment for theft and violent offenses. The percentage of those that received criminal punishment for violent offences (31.0%), in particular, was remarkably higher than that with those who idled time away but did not associate with delinquent friends (5.3%) (also higher than that with all the research subjects of concern associating with delinquent friends). With those who both associated with delinquent friends and had debt problems the percentage of those that received criminal punishment for theft was high, but no significant difference between those who associated with delinquent friends and those who did not associate with delinquent friends could be observed.

b. Association with delinquent friends

Fig. 7-3-3-3-9 shows the time when and the place where the association with delinquent friends began with those who had this problem (actual number of 125 persons).

Of 110 research subjects of concern for whom the time when and place where the association began was identified the percentage of those who were already associating with them before admission to juvenile training schools for the index delinquencies was higher at 68.2% (75 persons) than the percentage of those who began associating with them after their relevant discharge of 45.5% (50). With the former many began in hometowns (34.7% or 26 persons) and at schools (28.0% or 21 persons). These two places accounted for over 50%, even counting those falling into more than one category only once. In contrast to this, with the latter, the places where the association began significantly vary, and the association was made with a wide range of delinquent friends. Solving the problem on their relationships with friends in their hometown or at school is important to make them break away with delinquent friends when they already associated with them before admission, but when they started to associate with them after discharge, identifying these friends is difficult, therefore being sensitive to their relationships with friends is necessary.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-9 Beginning of association with delinquent friends

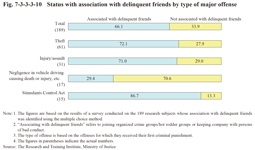

Fig. 7-3-3-3-10 shows the status with association with delinquent friends by type of major offense for which they received the first criminal punishment.

The percentage of those who associated with delinquent friends was remarkably high at 86.7% with those that received criminal punishment for Stimulants Control Act violations, followed by that with those that received criminal punishment for theft and injury/assault, both at approximately 70%, but that with those that received criminal punishment for negligence in vehicle driving causing death or injury, etc. was remarkably low at approximately 30%. Excluding negligence in vehicle driving causing death or injury, etc., which is unlikely to be committed in complicity, the problem of associating with delinquent friends was commonly observed, regardless of the type of offense, and was particularly serious with those that received criminal punishment for Stimulants Control Act violations.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-10 Status with association with delinquent friends by type of major offense

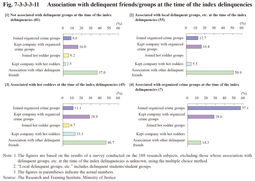

Fig. 7-3-3-3-11 shows details on the association with delinquent friends that the research subjects of concern had during the period between their relevant discharge and the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment by delinquency group that they were associated with. Of those that committed offenses after being discharged the number of those associated with organized crime groups at the time of the index delinquencies was small at seven, but four of which then joined organized crime groups after being discharged and another two kept company with organized crime groups even after their relevant discharge. In contrast to this, of those not associated with organized crime groups at the time of the index delinquencies, 22.2% either joined organized crime groups or had company with organized crime groups after being discharged (excluding those falling into more than one category) and 56.8% (46 persons (actual number excluding those falling into more than one category)) came to have some problematic associations after being discharged. At least with those that received criminal punishment after being discharged, many then eventually associated with delinquent groups, including organized crime groups, or other persons of bad conduct after being discharged, even if they did not have any association with delinquent groups at the time of the index delinquencies, and this possibly was a factor that led them to commit offenses.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-11 Association with delinquent friends/groups at the time of the index delinquencies

c. Debt, idling time away

Of the research subjects of concern for which data was available (189 persons), the percentage of those that had the problems of debt and idling time away after their relevant discharge and before the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment was relatively high at 34.4% (65) and 32.3% (61), respectively, and that of those that had at least one of these problems accounted for the majority at 54.0% (102). Fig. 7-3-3-3-12 shows the percent distribution of those that had financial problems, including debt problems and idling time away, etc., by type of offense for which they received the first criminal punishment.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-12 Percent distribution of research subjects of concern with problems of debt/idling time away by type of offense

Those that received criminal punishment for theft accounted for the highest proportion at 33.3%, followed by violent offenses at 19.6%, and then serious offenses (robbery) and drug offenses (Stimulants Control Act violations), both at 9.8%. Of “others” that for fraud was also high at 6.9%. Financial problems are connected with property offenses, including theft, etc., and are also considered to be connected with violent offenses and with serious offenses by combining theft and violent offenses (robbery) into one, etc.

(4) Analysis by Offense type

Next, problematic behavior, etc. observed after their relevant discharge and before the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment are examined. Fig. 7-3-3-3-13 shows the percentage of research subjects of concern that had problematic behavior, etc. by offense type.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-13 Problematic behavior, etc. after their relevant discharge by offense type

a. Theft offense type

With those belonging to the theft offense type (105 persons), associating with delinquent friends accounted for the highest proportion of all the types of problematic behavior, etc. at 70.5%, followed by debt problems at 37.1%, idling time away at 33.3%, and gambling addictions at 22.9%. This indicates that many of those belonging to the theft offense type had problems with employment and financial instability.

Next, of all criminal punishment involving theft, modus operandi, the motive, and their living status at the time of offense for the offenses in the first final judgment after their relevant discharge (theft that resulted in the greatest damage was selected in cases where more than one theft case was included in the judgment) are examined with those that belonged to both the theft delinquency group and theft offense type (70 persons) in thereby identifying the characteristics of those that repeated theft. Of those whose modus operandi of their delinquencies while juveniles was identified, the percentage of those whose modus operandi of the offense (See Fig. 7-3-2-7) was the same as that of their delinquencies while juveniles was 57.1%. By complicity status, the percentage of those that committed theft alone (37.1%) was lower, and the percentage of those that committed theft with one accomplice (41.4%) or with two accomplices (18.6%) both higher than that of all the research subjects that committed theft (See Fig. 7-3-2-8). In addition, of those whose time when their relationship with the accomplices began was identified, 62.5% began the relationships before admission to juvenile training schools for their index delinquencies, and of those whose accomplices were their “friends/acquaintances” (28 persons) the relationships of 22 persons were identified and of which six committed theft with the same accomplices as in their delinquencies while juveniles. The majority committed theft with the motive of being in need of living/amusement expenses, but with those with accomplices some participated in theft in order to maintain the relationship with the accomplices. These indicate their associating with delinquent friends (associating with them from when they were juveniles, in particular) to be connected with committing theft. Examining their living status at the time of the offenses revealed that those who were unemployed accounted for the high percentage at 45.7% (See Fig. 7-3-3-3-3 [1] for all the research subjects of concern) and those without fixed residences 20.0% (See Fig. 7-3-3-3-3 [1] (id.)), thus indicating instability in living bases to be a factor that led them to repeat theft. In addition, examining their attitudes toward theft revealed that some of them did not take theft very seriously (“money can be obtained quickly/easier than working”), some justified the act of theft (“necessary in my life (to live)”), and some did not have any hesitation in committing theft (“willing to steal whenever possible”), thus the characteristics including a lack of moral awareness and the motivation to work, etc. were observed.

b. Violent offense type

Of those belonging to the violent offense type (63 persons) the percentage of those that joined (or kept company with) organized crime groups was 47.6%, which was higher than that with those belonging to other offense types.

Of all criminal punishment involving violent offenses and with those belonging to both the violent delinquency group and violent offense type (37 persons), examining the background of the offenses in the first final judgments after their relevant discharge to identify the characteristics of those that repeated violent offenses revealed that of 19 research subjects of concern for whom data was available, six committed violent offenses on an impulse (unleashing their anger on victims, etc.), six used violence as a means (to obtain money, to prove their superiority over victims, etc.), and four due to the sense of the values of delinquent groups (placing priority on the honor of organized crime groups, etc.).

This indicates that those belonging to the violent offense type had the problems of associating with delinquent friends and their own capacity, including a lack of self-control and distorted way of thinking about violence, etc.

c. Drug offense type

With those belonging to the drug offense type (41 persons) the percentage of those that used drugs and associated with delinquent friends was remarkably high at 78.0% and 82.9%, respectively, and that of those with debt problems and who idled time away relatively high, being both at 34.1%. In addition, of all those belonging to the drug offense type (45 persons) only approximately 30% (12) committed drug offenses as a juvenile delinquency (belonging to the drug delinquency group) and approximately 70% (33) did not. This suggests the possibility that many started committing drug offenses after their discharge from juvenile training schools and it probably was because of an association with delinquent friends.

d. Sexual/traffic offense type

With those belonging to the sexual offense type (13 persons) and to the traffic offense type (52) the percentage of those with the problematic behavior of associating with delinquent friends or idling time away was lower than that with the total (See Fig. 7-3-3-3-6).

e. Serious offense type

Of those belonging to the serious offense type (17 persons) many associated with delinquent friends and had debt problems.

Examining the types of serious offenses in the first final judgments after their relevant discharge of 18 research subjects of concern belonging to the serious offense type (including those whose problematic behavior, etc. was not identified) revealed that one committed injury causing death (against relatives stemming from a request for money) and 17 robbery.

By the major type of violation (the offense that resulted in the greatest damage was selected in cases where more than one offense of the same type was involved; hereinafter the same in this subsection), there were eight cases of on-the-street robbery, two constructive robbery, and two “badger game” type robbery (initially started as the so-called badger game and resulted in robbery). By motive/cause, all but one case, in which case the research subject followed the lead of accomplices, were to obtain money and the background of these cases included debt (five cases), payment to organized crime groups or hot rodder groups (four), and unemployment/poverty (four). By the relationship with their victims they were non-acquaintances in 15 of 17 cases.

By employment status at the time of the serious offenses 44.4% were employed and by residential status 72.2% had residences, with the percentages both being low when compared to that with all the research subjects. By complicity status and relationship with accomplices, the complicity rate was high at 66.7% (See Fig. 7-2-1-1-12 for the complicity rate for non-traffic penal code offenses) and of those whose relationships with the accomplices were identified (10 persons) five committed serious offences in complicity with persons associated with organized crime groups or hot rodder groups, three with friends/acquaintances, and one each with a criminal groups and a colleague of gangsters. None were drinking alcohol at the time of the offenses, and of those using drugs two were inhaling paint-thinner and one using narcotics/opium.

Generally speaking, and in many cases they were with a background of unemployment, debt, and payments to delinquent groups, etc., hard pressed financially or in terms of personal relationships and thus robbed non-acquaintances of money with colleagues of delinquent groups, and thus many of them have the combined characteristics of both the theft offense type and violent offense type.

(5) Status during the period without offenses

Various factors that lead to offenses, etc. were analyzed in the above subsections. This subsection identifies the status during the period when they did not commit any offenses after their relevant discharge and before committing the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment, and discusses the factors that keep them from committing offenses.

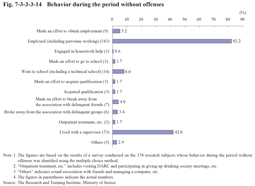

Fig. 7-3-3-3-14 shows the patterns of behavior of the research subjects during the period they did not commit any offenses after their relevant discharge and before the offenses for which they received their first criminal punishment. Those whose behavior during the period that they did not commit any offenses were identified (174) were examined using criminal case records by checking each applicable item. Of the research subjects of concern, 143 (82.2%) were employed and nine (5.2%) made the effort to obtain employment, thus 85.6% (excluding those included in more than one category) were employed or making the effort to obtain employment. Considering that only 52.4% of them were employed at the time of the offenses 85.6% was a remarkably high percentage, and thus being employed or making the effort to obtain employment are considered effective in preventing offenses.

At least 73 persons (42.0%) lived with their supervisors, which is a high percentage. Furthermore, considering that a large number of them no longer lived with their supervisors at the time of the offenses (SeeFig. 7-3-3-3-1 [2]), with juveniles/young people, appropriate life management through living with their supervisors is considered effective in preventing offenses.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-14 Behavior during the period without offenses

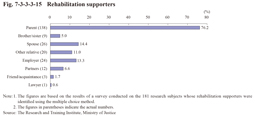

As described above, providing them with rehabilitation support, including from supervisors, contributes to their rehabilitation, although to a varying level. Fig. 7-3-3-3-15 shows the status of those supporting their rehabilitation and their breakdown (excluding volunteer probation officers) during the period they did not commit offenses.

Fig. 7-3-3-3-15 Rehabilitation supporters

Of 181 research subjects of concern whose status with rehabilitation support was identified using criminal case records, 171 (94.5%) had supporters during the period they did not commit any offenses, the high percentage confirmed the importance of that support. By the supporters, their parents were the largest in number at 138 (76.2%), followed by spouses at 26 (14.4%), and employers at 24 (13.3%). Parents accounted for the majority of the rehabilitation supporters, with the others being rather few. Living together with the parents that can supervise juveniles (the majority of their guarantors at the time of their relevant discharge; See Fig. 7-3-1-6) and support their rehabilitation is therefore considered important from the point of view of preventing offenses and providing rehabilitation support. In spite of this, the fact that the percentage of those who lived with their parents after their discharge was rather low (See Fig. 7-3-3-3-1) is considered to have promoted the risk of offending.

In addition, examining the number of supporters revealed that 65.2% had one supporter (each research item is counted as one supporter) and 29.3% two or more supporters, thus the majority of them had only one supporter (parent in most cases), and therefore the persons that supported their rehabilitation was rather limited.

Examining the changes in family relationships, etc. revealed that of 154 research subjects of concern for whom data was available, 19.5% (30 persons) married after their relevant discharge and before the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment, and in approximately 80% of those cases their spouses were pregnant or had already given birth at the time of their marriage, but approximately 40% subsequently got divorced or separated within a short period of time up to when they committed the offenses for which they received the first criminal punishment. Young offenders with a history of commitment to a juvenile training school strongly regarded the existence of their families, including spouses, etc., as a restraint on committing offenses (See Fig. 7-4-3-9), although instability in their family relationships with their spouses, etc., is considered to have weakened its effectiveness in preventing offenses.

Examining the problem of their association with delinquent friends revealed that only seven (4.0%) made the effort to break away from their association and six (3.4%) left delinquent groups (See Fig. 7-3-3-3-14). Considering that most of the research subjects of concern had a problem with associating with delinquent friends, the percentage was low. Taking into consideration that the research subjects of concern all eventually committed offenses and received criminal punishment, sufficient rehabilitation cannot be achieved keeping their association with delinquent friends intact, and they would refrain from offenses only for certain period of time.