1 Analysis of the subjects by history of protective measures and living status, etc.

(1) History of protective measures

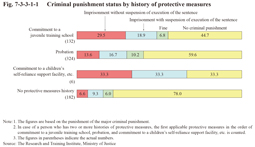

Fig. 7-3-3-1-1 shows the criminal punishment status by history of protective measures the research subjects received before being committed to a juvenile training school for an index delinquency. The percentage of those that received criminal punishment was higher with those with a history of protective measures, those with a history of commitment to a juvenile training school or children’s self-reliance support facility, etc., in particular, than with those without that history. In addition, the percentage of those sentenced to imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence was higher with those with a history of protective measures, those with a history of commitment to a juvenile school, in particular, than with those with that history. Furthermore, although the actual number of those only with a history of commitment to a children’s self-reliance support facility, etc. was small at six, the percentage of those who were sentenced to imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence was higher at approximately 30% than the percentage of those without a history of protective measures who were sentenced to imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence. At the time of the index delinquencies the persons subject to commitment to a juvenile training school was limited to juveniles aged 14 or older (the Juvenile Act/Juvenile Training Schools Act prior to revision by Act No. 68 of 2007), and protective measures used for juveniles younger than 14 were limited to probation or commitment to a children’s self-reliance support facility, etc.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-1 Criminal punishment status by history of protective measures

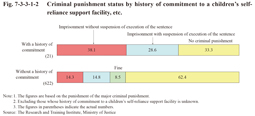

Fig. 7-3-3-1-2 shows the criminal punishment status with or without a history of commitment to a children’s self-reliance support facility, etc. of the total of those with a history of commitment to a children’s self-reliance support facility, etc. only and those with a history of commitment to a juvenile training school or placed under probation. The actual number of those with a history of commitment to a children’s self-reliance support facility, etc. was small at 21. Of them, however, the percentage of those that received criminal punishment was remarkably higher than those without the said history, while the percentage of those sentenced to imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence was similarly higher. Considering that the percentage of those belonging to the younger age groups is higher with juveniles accommodated in children’s self-reliance support facilities, etc. than with juveniles accommodated in juvenile training schools, in general (See Fig. 7-2-2-4), this then indicates that those requiring protection at a younger age will face difficulty in their subsequent reformation/rehabilitation.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-2 Criminal punishment status by history of commitment to a children’s self-reliance support facility, etc.

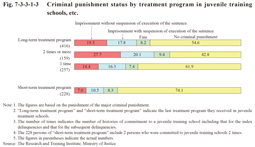

Next, attention is paid to the treatment programs they received in juvenile training schools, etc. Fig. 7-3-3-1-3 shows the criminal punishment status by treatment program and the number of histories of commitment to a juvenile training school. Some of the research subjects received the protective measure of commitment to a juvenile training school again after their relevant discharge, and hence the last treatment program they received and the number of histories of commitment to a juvenile training school are included. By treatment program, the percentage of those that received criminal punishment was lower with those that received short-term treatment programs (refers to general short-term treatment programs and special short-term treatment programs; See Subsection 2, Section 4, Chapter 1, Part 3) than with those that received long-term treatment programs. Those that received short-term treatment programs are considered to have rather simple or relatively less serious problems and more likely to be promptly reformed and hence providing enhanced education/guidance, etc. at the stage when the problems are less serious is considered effective to avoid their receiving criminal punishment in the future. In addition, the percentage of those that received criminal punishment was high with those who have been committed to a juvenile training school more than once, and hence guidance for those readmitted to juvenile training schools is also considered very important.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-3 Criminal punishment status by treatment program in juvenile training schools, etc.

(2) Status in juvenile training schools

Disciplinary actions, including admonitions and penitence, etc., can be taken against those that violated the order of juvenile training schools. Fig. 7-3-3-1-4 shows the criminal punishment status by the number of disciplinary actions taken against the research subjects while in juvenile training schools. Both the percentage of those that received criminal punishment and the percentage of those sentenced to imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence rose as the number of disciplinary actions increased. Various types of guidance for the reformation/rehabilitation of juveniles are provided in juvenile training schools and violation of discipline is deemed to contradict a sincere attitude toward reformation/rehabilitation. The seriousness of their willingness to rehabilitate themselves is therefore considered to be related to their subsequent acts that result in criminal punishment.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-4 Criminal punishment status by number of disciplinary actions taken in juvenile training schools

(3) Home environment

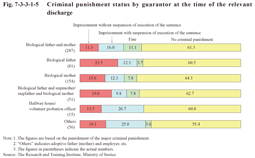

Fig. 7-3-3-1-5 shows the criminal punishment status by guarantor at the time of the relevant discharge. No significant differences were observed in the criminal punishment status regardless of who the guarantors were.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-5 Criminal punishment status by guarantor at the time of the relevant discharge

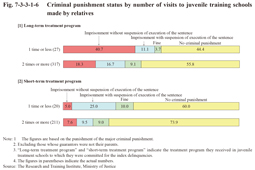

Next, attention is paid to the status with visits while in juvenile training schools in thereby identifying their relationship with their guarantor. Fig. 7-3-3-1-6 shows the criminal punishment status of those whose guarantor was their parents by the number of visits made by their relatives while in juvenile training schools (including visits made by relatives other than their guarantors). With those that received short-term treatment programs no significant difference was observed in either the percentage of those that received criminal punishment or the percentage of those sentenced to imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence depending on the number of visits. With those that received long-term treatment programs, however, the percentage of those sentenced to imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence was remarkably higher with those that did not have any visits from relatives and those that had only one visit than with those that had two or more visits (the average number of visits made by relatives in cases where the guarantors were their parents was approximately four with those that received short-term treatment programs and approximately eight with those that received long-term treatment programs). Visits to juvenile training schools serve as an important opportunity for the research subjects to maintain good relationships with their families and make adjustments to their family relationships and are effective in preparing for their reintegration back into society. Juvenile training schools therefore request their guardians, etc. to make visits in cases where no visit has taken place. The number of visits is affected by the distance between the residences of the guarantors and the juvenile training schools. In many cases, however, no visit for a long time makes maintenance of and adjustments to family relationships etc. difficult, and eventually affects the stability of juveniles’ lives after being discharged, thus tends to lead them to the acts that result in criminal punishment.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-6 Criminal punishment status by number of visits to juvenile training schools made by relatives

(4) Living status during parole supervision period

a. Employment status

Fig. 7-3-3-1-7 shows the criminal punishment status by employment status at the time of termination of their parole supervision (parole supervision after the relevant discharge (on parole); hereinafter the same in this subsection). The percentage of those that received criminal punishment was higher with those that were unemployed at the time of termination of their parole supervision than with both those that were employed and those that were students/pupils, etc. Being unemployed is therefore considered to be a risk factor in repeating offenses.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-7 Criminal punishment status by employment status at the time of termination of parole supervision

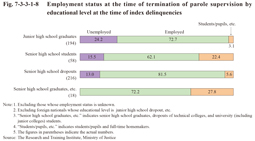

Next, factors that affected employment status are examined. Fig. 7-3-3-1-8 shows the employment status, etc. at the time of termination of parole supervision by educational level at the time of the index delinquencies. As difficulty in obtaining employment differs depending on their educational level in general (See Fig. 7-1-4), the percentage of research subjects that were unemployed also declined as their educational level rose. Being unemployed is more likely to result in criminal punishment as mentioned above, and therefore providing juvenile/young offenders with rather low educational levels and who are expected to face difficulty in obtaining employment with employment support and making high school graduate equivalency examinations available in corrective institutions are considered important.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-8 Employment status at the time of termination of parole supervision by educational level at the time of index delinquencies

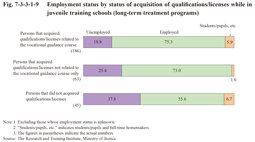

In addition, Fig. 7-3-3-1-9 shows the employment status at the time of termination of parole supervision of the research subjects that received long-term treatment programs by their status of acquisition of qualifications/licenses while in juvenile training schools. The percentage of those that were unemployed was 37.8% with those that did not acquire any qualification/license, but was low at 25.4% with those that acquired qualifications/licenses not related to the vocational guidance course individually assigned to them only, and 18.8% with those that acquired qualifications/licenses related to their vocational guidance course. Examining their occupation at the time of termination of parole supervision revealed that not all the qualifications, etc. that they acquired while in juvenile training schools directly contributed to their employment, but vocational guidance, etc. in juvenile training schools is still considered effective to a certain extent, for instance by raising their motivation to gain employment and thus become more independent, etc.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-9 Employment status by status of acquisition of qualifications/licenses while in juvenile training schools (long-term treatment programs)

b. Reason for termination of parole supervision

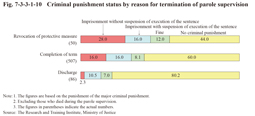

Fig. 7-3-3-1-10 shows the criminal punishment status by reason for termination of parole supervision. The percentage of those that subsequently received the criminal punishment of imprisonment without suspension of execution of the sentence was high with those who had their parole supervision revoked (due to repeat delinquencies, etc.), but with those that were granted discharge (those that were deemed unlikely to repeat offenses and therefore discharged before completion of their term of parole supervision) the percentage was extremely low and the percentage of those that did not receive criminal punishment high. This indicates that stable life condition during the parole supervision period after discharge from juvenile training schools is a significant factor to prevent subsequent criminal punishment.

Fig. 7-3-3-1-10 Criminal punishment status by reason for termination of parole supervision