| Previous Next Index Image Index Year Selection | |

|

|

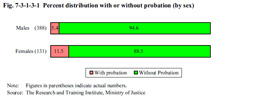

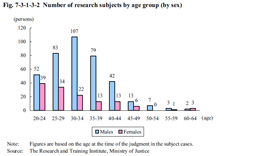

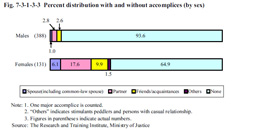

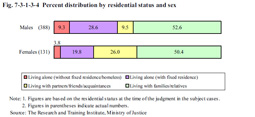

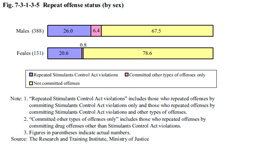

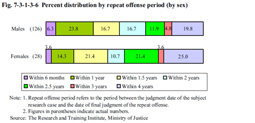

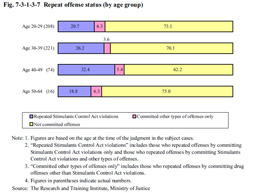

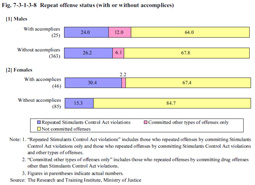

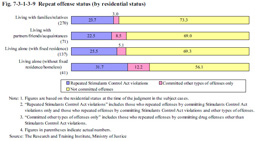

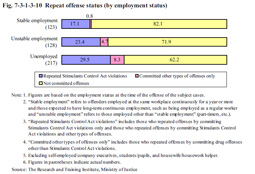

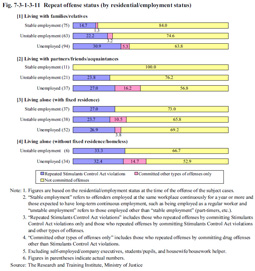

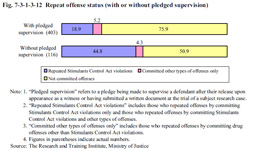

3 Stimulants (1) Overview of subject cases and research subjects519 stimulants offenders, consisting of 74.8% males and 25.2% females, were selected as research subjects, as described earlier. With regard to sentencing at the time of the first suspension of execution of the sentence, an imprisonment period of one year and six months was dominantly high with 401 persons (77.3%) and the period of suspension of execution of the sentence of three years was also dominantly high with 398 persons (76.7%). Fig. 7-3-1-3-1 shows the percent distribution of research subjects both with and without probation. Persons who were placed under probation accounted for 6.9% (36 persons) of the total. The rate of those who were placed under probation was slightly higher for females than males, indicating an opposite trend to the theft cases. Fig. 7-3-1-3-1 Percent distribution with or without probation (by sex) Fig. 7-3-1-3-2 shows the number of research subjects by age group.Unlike theft cases, among males, the number of subjects aged 30 to 39 was the largest in number then decreasing as the age of the group rose. Among females, the number of those aged 20 to 29 was the largest in number then decreasing as the age of the group rose. Fig. 7-3-1-3-2 Number of research subjects by age group (by sex) Fig. 7-3-1-3-3 shows the percent distribution of research subjects both with and without accomplices.Although the proportion of persons “without accomplices” was high overall, over 1/3 of females were “with accomplices,” and the proportion of those having a partner as the accomplice was especially high. Fig. 7-3-1-3-3 Percent distribution with and without accomplices (by sex) Fig. 7-3-1-3-4 shows the percent distribution of research subjects by residential status.Overall the proportion of persons “living with families/relatives” was high (52.0%). With females the proportion of persons “living with partners/friends/acquaintances” was remarkably high at over 1/4 when compared with males. Fig. 7-3-1-3-4 Percent distribution by residential status and sex (2) Repeat offense statusThe attributes of the research subjects and the circumstances of the offenses, etc. of the subject research cases, and whether or not they repeated offenses, will be compared and discussed below. a. Overall status First, Fig. 7-3-1-3-5 shows the repeat offense status for all the research subject stimulants offenders. The number of persons who repeated Stimulants Control Act violations (including those who repeated offenses by committing Stimulants Control Act violations only and those who repeated offenses by committing Stimulants Control Act violations and other type of offenses; hereinafter referred to as “repeat offenses for Stimulants Control Act violations” in this section) was 128 persons (24.7%) and the number of those who committed other types of offenses only was 26 (5.0%). The repeat offense rate was higher for males than females. In addition, the majority of repeat offenses committed by both male and female repeat offenders were Stimulants Control Act violations. Notably, of 28 female repeat offenders, all except for one committed Stimulants Control Act violations as the repeat offense. Fig. 7-3-1-3-5 Repeat offense status (by sex) Fig. 7-3-1-3-6 shows the repeat offense period for males and females who repeated offenses.Although the repeat offense period is slightly longer than in theft cases, the majority of those who repeated offenses did so within two years and then were convicted in final judgments. The repeat offense period tended to be shorter for males than females. Fig. 7-3-1-3-6 Percent distribution by repeat offense period (by sex) b. Analysis of repeat offense status under various conditionsFig. 7-3-1-3-7 shows repeat offense status by age group. Except for the age groups 50 or older, the repeat offense rate for Stimulants Control Act violations increased as the age of the group rose. Fig. 7-3-1-3-7 Repeat offense status (by age group) Fig. 7-3-1-3-8 shows repeat offense status both with and without accomplices among the subject research cases.For males no significant differences can be seen between the repeat offense rate of those with accomplices and that of those without. For females, however, the rate of those “with accomplices” is remarkably high, being about twice that of those “without accomplices.” As described earlier, the rate of persons “with accomplices” was high for female research subjects, suggesting quite a few start using stimulants because of the influence of others, such as in being encouraged to do so by others. Such persons are considered to be more likely to repeat Stimulants Control Act violations. Fig. 7-3-1-3-8 Repeat offense status (with or without accomplices) Fig. 7-3-1-3-9 shows repeat offense status by residential status.Although the repeat offense rate was the highest among persons “living alone (without fixed residence/homeless),” variations in the repeat offense rate according to residential status were smaller than for theft cases (See Fig. 7-3-1-2-13). Fig. 7-3-1-3-9 Repeat offense status (by residential status) Fig. 7-3-1-3-10 shows repeat offense status by employment status.Similar to theft cases (See Fig. 7-3-1-2-14), the repeat offense rate increased as employment status became less stable. Fig. 7-3-1-3-10 Repeat offense status (by employment status) Residential status and employment status were also examined in combination. Fig. 7-3-1-3-11 shows repeat offense status by residential/employment status (there was no person “living alone (without fixed residence/homeless)” with “stable employment”).The repeat offense rate among those “living alone (with fixed residence)” and “living alone (without fixed residence/homeless)” was generally higher than for those “living with families/relatives,” with the impact of the differences in employment status on the repeat offense rate being small. For those “living with families/relatives,” however, the repeat offense rate of those with “stable employment” was relatively low, while the repeat offense rate of those “without stable employment” and “unemployed” did not differ significantly from those “living alone (with fixed residence)” and “living alone (without fixed residence/homeless).” That is to say, if the residential status of a stimulants offender is unstable, the risk of them for repeating offenses is high, regardless of their employment status. The risk of repeat offenses tended to remain high, even with those with a stable residence, as long as employment status was unstable. Fig. 7-3-1-3-11 Repeat offense status (by residential/employment status) Fig. 7-3-1-3-12 shows repeat offense status both with and without pledged supervision.Although the number of persons “with pledged supervision” among stimulants offenders was high at over 3/4, the repeat offense rate of persons “without pledged supervision” was still remarkably high when compared to those “with pledged supervision.” The repeat offense rate for Stimulants Control Act violations by those “without pledged supervision” was more than twice that of those “with pledged supervision.” Including other types of repeat offenses, about 1/2 of them repeated offenses. Fig. 7-3-1-3-12 Repeat offense status (with or without pledged supervision) Pledged supervision and employment status were then examined in combination. Fig. 7-3-1-3-13 shows repeat offense status both with and without pledged supervision and by employment status.The repeat offense rate of those “without pledged supervision” was generally significantly high when compared with those “with pledged supervision.” Although the repeat offense rate for Stimulants Control Act violations of those “without pledged supervision” and “with stable employment” was low (less than half) when compared with those “with unstable employment,” it was high when compared with those who were “unemployed” but “with pledged supervision.” This then indicates that the existence of someone to pledge to supervise stimulants offenders serves as a deterrent to repeat offenses, as it does in the case of theft offenders. Fig. 7-3-1-3-13 Repeat offense status (with or without pledged supervision, by employment status) Fig. 7-3-1-3-14 shows repeat offense status both with and without association with Boryokudan, etc. (refers to being regular members, quasi-members, or affiliates of Boryokudan, violent right wing groups, hot rodders, and other local violent groups; hereinafter the same in this section) at the time of the offense of the subject research cases.The risk of repeat offenses varies significantly for stimulants offenders depending on whether or not they are associated with Boryokudan, etc. About 40% of persons associated with Boryokudan, etc. repeated offenses for Stimulants Control Act violations. Including the other types of repeat offenses, over 1/2 of the total repeated offenses. For stimulants offenders, breaking away from Boryokudan, etc. is an important factor in preventing repeat offenses. Fig. 7-3-1-3-14 Repeat offense status (with or without association with Boryokudan, etc.) Lastly, Fig. 7-3-1-3-15 shows repeat offense status both with and without probation.The repeat offense rate of persons placed under probation was slightly higher than for those not placed under probation. As described in the subsection on theft cases, however, since probation is granted to those with a relatively high risk of repeat offenses to begin with, the fact that the repeat offense rate of persons placed under probation remained at almost the same level as those not placed under probation could be considered to be proof of the effectiveness of probation in reformation/rehabilitation and thus in preventing repeat offenses. (Since the number of stimulants offenders placed under probation was small in this research (total of 36 persons), detailed analysis could not be carried out in the same way as was done for theft offenders. In addition, the suspended execution revocation rate for the repeat offense of those placed under probation was 30.6%, and those not placed under probation was 22.6%.) Under the Offenders Rehabilitation Act, anyone with the tendency to repeat drug use who is placed under probation is obliged to participate in a stimulants offenders treatment program including quick drug screen testing as a special condition of supervision, with bad-conduct measures possibly being taken if they fail to do so. The expectation is that the effectiveness of probation in reformation/rehabilitation and repeat offense prevention will improve with this system in the future. Fig. 7-3-1-3-15 Repeat offense status (with or without probation) (3) ConclusionAbout 30% of research subject stimulants offenders repeated offenses, with over 80% of the repeated offenses being for Stimulants Control Act violations. The rate of those “with accomplices” was clearly higher for females than males, with the repeat offense rate of those “with accomplices” tending to be quite high. Although residential status and employment status are also influential factors in repeat offenses among stimulants offenders, the differences in the repeat offense rate by residential status was smaller than for theft offenders, and the impact of employment status on the possibility of repeat offenses limited: the risk of repeat offenses was high if residential status was unstable, regardless of employment status. As with theft offenders, the existence of someone to pledge supervision was found to be a significant preventive factor against repeat offenses for stimulants offenders. In addition, having relationships with Boryokudan, etc. was a quite significant risk in repeating offenses for stimulants offenders. |