| Previous Next Index Image Index Year Selection | |

|

|

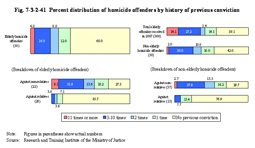

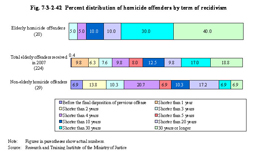

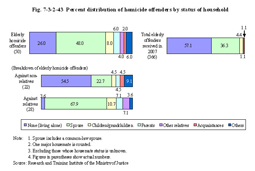

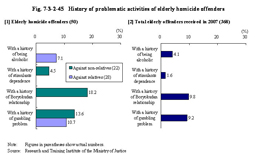

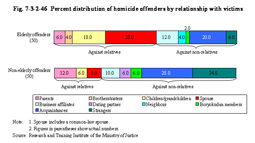

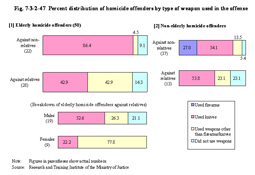

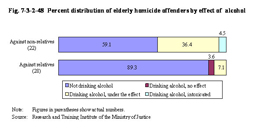

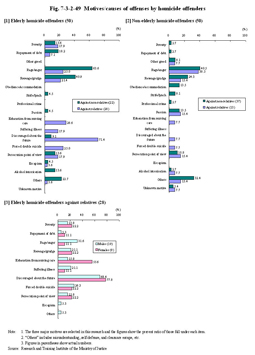

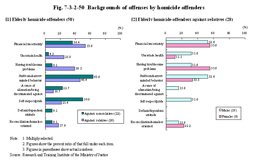

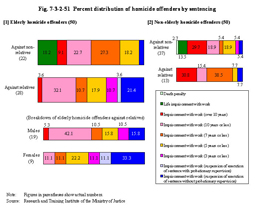

4 Homicide As shown in 2 of Section 1 and 2 of Section 2 in Chapter 2 the number of elderly (hereinafter referred to as “elderly homicide offenders” in this sub-section) cleared/prosecuted for serious homicide (refers to homicide or homicide at the scene of a robbery (including attempts); hereinafter the same in this sub-section) is on an increasing trend, but with the actual number being small. The number of elderly homicide offenders received and prosecuted by Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office (head office only) in 2007 was only two. Therefore, the research subjects for homicide cases were all 50 elderly homicide offenders received by Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office (head office only) during the period of 1998 and 2007 who were convicted at Tokyo District Courts and whose criminal case documents were available. In order to find the characteristics of elderly homicide offenders, a. Comparison of the attributes with those of the total elderly offenders newly received in 2007 (hereinafter referred to as “total elderly offenders received in 2007” in this sub-section) described in 1 of this section b. Comparison of the modus operandi with that of newly received homicide offenders less than 65 years of age at the time of reception (hereinafter referred to as “non-elderly homicide offenders” in this sub-section) c. Comparison of the attributes and modus operandi between those who had committed homicide against relatives (hereinafter referred to as “homicide (offenders) against relatives” in this part) and those who committed homicide against non-relatives (hereinafter referred to as “homicide (offenders) against non-relatives” in this part) were made in the analysis. In order to make a comparison with the 50 elderly homicide offenders, 50 non-elderly homicide offenders were selected as research subjects from those who were convicted at Tokyo District Courts in 2006 and 2007 in the order of date of conviction from latest to earliest. Although the year in which the offenses were committed differ among elderly homicide offenders, total elderly offenders received in 2007 and non-elderly homicide offenders, comparisons were made to help in roughly understanding the general characteristics of elderly homicide offenders. (2) Cases of elderly homicide offenders Five typical cases of elderly homicide offenders are given below. [1] A case of attempted homicide against a husband due to exhaustion from nursing care and financial uncertainty Female aged 69. No previous conviction/disposition. The offender retired from work just before the case due to exhaustion from nursing her husband aged 70 with dementia. She also had financial uncertainty due to a reduced income. The offender attempted homicide against her husband using an elastic band and a wrapping cloth, but gave up along the way. Sentenced to imprisonment with work for two years and six months, granted suspension of execution of sentence for three years. [2] A case of forced double suicide as a result of being distressed by illness and a large sum of debt Male aged 67. No previous conviction/disposition. In addition to physical deterioration the offender had a debt of 10 million yen due to a slump in his own business. His wife was in her 50s and had chronic diseases and he was discouraged about the future. The offender was determined to commit a forced double suicide and killed his wife, but his own suicide ended in failure. Sentenced to imprisonment with work for three years. [3] A case of growing discontent against family members for becoming uncomfortable at home after retiring Male aged 66. The offender had one previous conviction (injury through negligence in the pursuit of a social activity 35 years ago). During a long period of being posted away from his family for work the offender started to drink heavily. After retiring and returning home he felt uncomfortable in the house and started wandering around parks, watching horse racing, and drinking alcohol. His wife was in her 60s and became worried and decided to consult a doctor about her husband for alcoholism. The offender got angry and slashed her. He failed to kill her, but the offender was divorced afterwards. Sentenced to imprisonment with work for three years. [4] An enraged case at pride being hurt while drinking Male aged 70. No previous conviction/disposition. The offender invited a neighbor in his 40s to the offender's house. While drinking the neighbor made a derogatory comment about people at a bunkhouse where the offender used to work. The offender felt his past was being disrespected and stabbed him to death in a rage. Sentenced to imprisonment with work for 10 years. [5] A case of offenders with repeat offenses since juvenile Male aged 67. The offender had 10 previous convictions and had been imprisoned a number of times. The offender had been committing theft and violent offenses since juvenile with his last conviction being for injury 16 years ago. The offender quit his job as a construction worker, spent all his money on horse racing, and was living on the street after leaving a common lodging house. While the offender was telling his life story to a homeless the homeless person abused him as being annoying. The offender got enraged and used a cutter knife to slash him in the neck, killing him. Sentenced to imprisonment with work for 10 years. (3) Comparison of attributes a. Type of offense and distribution by sex The type of offense committed by elderly homicide offenders included homicide with 45 persons (of which 18 were attempts) and homicide at the scene of a robbery with five persons (of which two were attempt). By sex, 41 were males, nine females, with all the cases of homicide at the scene of a robbery having been recommitted by males. On the other hand, the type of offence committed by non-elderly homicide offenders included homicide with 46 persons (of which 23 were attempts), homicide at the scene of a robbery with two persons (of which one was an attempt), and being an accomplice to homicide with two persons (both attempts). By sex, 40 persons were males, 10 persons were females, the homicide at the scene of a robbery cases were committed by a male and a female, and all cases of being an accomplice to homicide were committed by males. Among elderly homicide offenders, homicide against relatives were committed by 28 persons, homicide against non-relatives by 22 persons, and all cases by females were homicide against relatives. Among non-elderly homicide offenders, homicide against relatives were committed by 13 persons, homicide against non-relatives by 37 persons, and six cases of homicide against relatives were committed by females. b. Previous convictions (a) Previous convictions/dispositions/imprisonment Fig. 7-3-2-41 shows the percent distribution of homicide offenders by history of previous conviction. Among elderly homicide offenders, the number of previous convictions tends to be small (18 convictions at maximum), as seen by the percent ratio of “no previous conviction” being high and that of 11 or more convictions was low, when compared to total elderly offenders received in 2007. However, the number of previous convictions differs significantly between homicide offenders against relatives and homicide offenders against non-relatives. More than 80% of homicide offenders against relatives had “no previous conviction” (four convictions at maximum) while only 27.3% of homicide offenders against non-relatives had “no previous conviction”. In addition, for homicide offenders against non-relatives, the percent ratio of “no previous conviction” was lower than that of total elderly offenders received in 2007. Of five persons committing homicide at the scene of a robbery, one person had “no previous conviction”, two had one previous conviction, one had four convictions, and one had five convictions. Among elderly female homicide offenders, one person had a previous record of suspension of prosecution for shoplifting, but all had “no previous conviction”. Among total elderly offenders received in 2007, the percent ratio of “no previous imprisonment ” was 64.4%, “one imprisonment” was 7.1%, “two or more imprisonments” was 28.5% while among elderly homicide offenders it was 82.0%, 2.0%, and 16.0%, respectively. Fig. 7-3-2-41 Percent distribution of homicide offenders by history of previous conviction (b) Age at the time of first convictionAmong 20 elderly homicide offenders with previous convictions, the age at the time of their first conviction was low, when compared to total elderly offenders received in 2007. The percent ratio of those who were juvenile at the time of their first conviction was only 3.6% among total elderly offenders received in 2007 but 15.0% among elderly homicide offenders. In addition, all the previous convictions were at less than 65 years of age, with no one being convicted for the first time at an elderly age. (c) Term of recidivism Fig. 7-3-2-42 shows the period from the date of the latest previous conviction to the date of committing the offense subject to this research (hereinafter referred to as the “term of recidivism” in this sub-section) among those with previous convictions. Among elderly homicide offenders, those with the term of recidivism of 20 years or over accounted for 70% with the term of recidivism tending to be longer when compared to total elderly offenders received in 2007. The term of recidivism of those with one or two previous convictions and homicide offenders against relatives with previous convictions were all 20 years or longer, while that of three persons who had committed homicide at the scene of a robbery, excluding one with five previous convictions, were all 25 years or longer. The percent ratio of elderly homicide offenders with the term of recidivism of less than five years was 10% (two persons) while that of non-elderly homicide offenders was over 50% (15 persons). Among elderly homicide offenders, no one was under suspension of execution of sentence or on parole at the time of the offense subject to this research. Fig. 7-3-2-42 Percent distribution of homicide offenders by term of recidivism c. Living situation, etc.(a) Residential status, etc. i. Residential status Among total elderly offenders received in 2007, the percent ratio of those who had no stable residence at the time of the offense was 6.8% and that of those who were homeless was 12.3%, while no elderly homicide offender had no stable residence and only one elderly homicide offender was homeless. Among elderly homicide offenders, homicide offenders against relatives all lived in their own residence. ii. Status of housemate Fig. 7-3-2-43 shows the percent distribution of homicide offenders by status of household at the time of the offense. Many of homicide offenders against relatives naturally lived with their relatives. Homicide offenders against non-relatives tend to be similar to total elderly offenders received in 2007 regarding status of housemate and the majority were living alone. Dividing homicide offenders against non-relatives into groups of those with no previous conviction or one previous conviction (10 persons) and those with more than one previous conviction (12 persons) reveals that the percent ratio of those living alone was 30.0% for the former group and 75.0% for the latter group. Those with multiple previous convictions tended to have been living alone. 60.0% of homicide offenders against non-relatives were not keeping in touch with their relatives. Fig. 7-3-2-43 Percent distribution of homicide offenders by status of household iii. Marital statusThe percent ratio of elderly homicide offenders who were single at the time of the offense was 26.0%, close to that of total elderly offenders received in 2007 (23.2%). There were significant differences, however, between that of homicide offenders against relatives with 14.3% and that of elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives with 40.9%. The percent ratio of elderly homicide offenders against relatives who were “married” was 78.6% while that of elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives was only 27.3%, less than that of those who were “divorced (excluding bereaved)” at 31.8%. Among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives who were married at the time of the offense, the percent ratio of those with “no previous conviction” or one previous conviction was 50.0% while that of those with two or more convictions was 8.3%. iv. Association with non-relatives The percent ratio of those who had association with non-relatives at the time of the offense (excluding those with unknown status) was 68.2% among total elderly offenders received in 2007 and rather high at 90.2% among elderly homicide offenders. Among elderly homicide offenders against relatives, all but one male had association with non-relatives. (b) Financial situation i. Source of income Fig. 7-3-2-44 shows the source of income at the time of the offense used in this research. Although the trends with source of income were similar between elderly homicide offenders and total elderly offenders received in 2007, many elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives were receiving welfare aid while many elderly homicide offenders against relatives were receiving pensions. Fig. 7-3-2-44 Source of income of elderly homicide offenders ii. DebtThe percent ratio of those who had debt was higher among elderly homicide offenders than total elderly offenders received in 2007, with the amount of debt also tending to be higher among elderly homicide offenders. There was no difference in the percent ratio of those with debts between elderly homicide offenders against relatives and elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, but the percent ratio of those who had debts of over 10 million yen was higher among elderly homicide offenders against relatives at 12.5% than elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives at 5.9%. (c) Living stability i. Employment status There was a significant difference in the percent ratio of those “with stable employment period” between homicide elderly offenders against relatives at 100% and homicide offenders against non-relatives at 54.5%. Among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, the percent ratio of those who had no previous conviction or one previous conviction “with stable employment periods” was 80.0%, while that of those who had two or more previous convictions “with stable employment periods” was 33.3%. ii. Health status The percent ratio of those “with disorders/disabilities” was over 50% among both elderly homicide offenders against relatives and elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, at the same level as that among total elderly offenders received in 2007. iii. History of problematic activities Fig. 7-3-2-45 shows the history of problematic activities of elderly homicide offenders. No elderly female homicide offenders had a history of problematic activities. 7.1% (10.5% among males) of elderly homicide offenders against relatives had a history of being alcoholics while none of elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives had that history. Conversely, some elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives had histories of stimulant dependence or in Boryokudan while none of elderly male homicide offenders against relatives had that history. Fig. 7-3-2-45 History of problematic activities of elderly homicide offenders iv. Educational background (highest education received)The percent ratio of those having the educational background (highest education received) of high school (graduated) or higher was 13.6% among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, while, among elderly homicide offenders against relatives, 42.9% had the educational background (highest education received) of high school (graduated) or higher and 17.9% had that of college (graduated) or higher. By sex, the majority of elderly female homicide offenders against relatives had the educational background (highest education received) of high school (graduated) and 1/4 of elderly male homicide offenders against relatives had that of college (graduated) or higher. Elderly homicide offenders against relatives tended to have higher educational background when compared to total elderly offenders received in 2007. (4) Comparison of modus operandi, etc. a. Relationship with victim As shown in Fig. 7-3-2-46, the majority (56.0%) of victims (those who had been inflicted the most serious damage were counted in case multiple victims existed) of offenses committed by elderly homicide offenders were their relatives. Among elderly female homicide offenders, all the victims were their relatives. Among elderly male homicide offenders, 46.3% of the victims were relatives. All the victims of homicide at the scene of a robbery were non-relatives. Among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives and elderly female homicide offenders, nearly 90% of victims were males. Conversely, among elderly male homicide offenders against relatives, over 70% of victims were females. In addition, 42.0% of victims of offenses committed by elderly homicide offenders were elderly aged 65 or older. On the other hand, among non-elderly homicide offenders, about 3/4 (74.0%) of victims were non-relatives with the percent ratio of victims being strangers being higher than cases by elderly homicide offenders. By sex, 17.5% of victims of non-elderly male homicide offenders were relatives while 60.0% of victims of non-elderly female homicide offenders were relatives. None of the victims of homicide at the scene of a robbery and accessoryship to homicide cases were offenders' relatives. About 10% of victims were elderly. Fig. 7-3-2-46 Percent distribution of homicide offenders by relationship with victims b. Modus operandi, etc. of offenses(a) Type of weapon Fig. 7-3-2-47 shows the percent distribution of homicide offenders by type of weapons used in the offense. Over 1/4 (10 persons) of non-elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives used firearms. None of the elderly homicide offenders used firearms. Nearly 90% of elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives used knives, while only about 40% of elderly homicide offenders against relatives did. Only a small number of elderly female homicide offenders against relatives used knives with nearly 80% of them using blunt instruments or rope. Fig. 7-3-2-47 Percent distribution of homicide offenders by type of weapon used in the offense (b) Effect of alcohol at the time of the offenseFig. 7-3-2-48 shows the percent distribution of elderly homicide offenders by effect of alcohol at the time of the offense. Less than 10% of elderly homicide offenders against relatives were under the effect of alcohol but about 40% of those against non-relatives were. Among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, all cases of homicide at the scene of a robbery were “not drinking alcohol”, but after excluding these cases the majority at 52.9% were under the effect of alcohol. Fig. 7-3-2-48 Percent distribution of elderly homicide offenders by effect of alcohol (c) Consummation rateThe consummation rate was higher among elderly homicide offenders against relatives at 71.4% (78.9% for elderly male homicide offenders) than among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives at 45.5% (60.0% for homicide at the scene of a robbery cases). The similar trends was observed with non-elderly homicide offenders, at 76.9% against relatives and at 37.8% against non-relatives. (d) Accomplices Among non-elderly homicide offenders, eight persons (five cases) had committed offenses with accomplices, of which seven persons (four cases) were involved in organized crimes. However, among elderly homicide offenders, only one female offender had an accomplice and none were involved in an organized crime. Two elderly homicide offenders (six non-elderly homicide offenders) had relationships with Boryokudan at the time of the offenses, but the motives/causes in these cases were due to their pride in being group leaders of Boryokudan and they were not involved in organized crimes. c. Motives/causes, etc. (a) Motives/causes Fig. 7-3-2-49 shows the motives/causes of the offenses. Figure [1] shows that the percent ratio of “anger/rage” was the most common among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives followed by “revenge/grudge”, while “discouraged about the future” was the most common among elderly homicide offenders against relatives followed by “exhaustion from nursing care”. The motives/causes of homicide at the scene of a robbery did not include “anger/rage” or “revenge/grudge”, but were biased toward financial reasons such as “repayment of debts” with four persons and “poverty” with two persons. Therefore, after excluding these cases, over 80% of elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives had “anger/rage” and over 50% had “revenge/grudge” as the motive/cause. Figure [3] shows that the motives/causes of elderly homicide offenders against relatives were significantly different for male and females with regard to “anger/rage” and “exhaustion from nursing care”. The former was dominantly higher among males while the latter was dominantly higher among females. On the other hand, figure [2] shows that “anger/rage” was the most common motive/cause among non-elderly homicide offenders both against relatives and against non-relatives, followed by “revenge/grudge”. Of financial motives, “poverty” and repayment of debts” were common among elderly homicide offenders, while “other greed” was common among non-elderly homicide offenders. “Passion” was not common among elderly homicide offenders but was rather common among non-elderly homicide offenders both against relatives and against non-relatives. Motives/causes related to organized crime groups (“obedience/accommodation”, “professional crime”, “strife/lynch”) were noticeable among non-elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives. Upon examining these cases in detail, of nine elderly female homicide offenders, the victims of seven of the offenders (77.8%) had diseases, while the victims of three of the offenders who had committed homicide against their children all had psychiatric disorders. Of six cases of elderly male homicide offenders against their children, half the victims had psychiatric disorders. Among 13 non-elderly homicide offenders against relatives, aversion to scolding or violence from their parents or spouses were relatively common, and their motives/causes significantly differred from those of elderly homicide offenders against relatives, including such motives/causes as that a child had became a nuisance in a relationship with a new partner, or the jealousy of their spouses, etc., which were rare among elderly offenders. More elderly homicide offenders attempted suicide after the offense than non-elderly homicide offenders. Nearly half elderly homicide offenders had planned to commit suicide. Fig. 7-3-2-49 Motives/causes of offenses by homicide offenders (b) Backgrounds of offensesFig. 7-3-2-50 shows the thinking patterns, etc. characteristic of elderly that may have been background factors of their offenses. “Stubborn/narrow-minded behavior” and “self-respect/pride” were the most common, in that order, among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, while “financial uncertainty” and “stubborn/narrow-minded behavior” were the most common, in that order, among elderly homicide offenders against relatives. Items that differed by 10 points or more in the percent ratio among the two groups included “stubborn/narrow-minded behavior”, “self-respect/pride”, and “a sense of alienation/being discriminated against”, which were higher among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, and “financial uncertainty”, “uncertain health”, and “having troublesome problems”, which were higher among elderly offenders against relatives. Furthermore, by sex, “a sense of alienation/being discriminated against” and “self-respect/pride” were found only with males, while “having troublesome problems” was more common with females. Fig. 7-3-2-50 Backgrounds of offenses by homicide offenders d. SentencingFig. 7-3-2-51 shows the percent distribution of homicide offenders by sentence. The sentences for those who had committed homicide against relatives tend to be less severe than those against non-relatives, both with elderly homicide offenders and non-elderly homicide offenders. Especially among elderly female homicide offenders against relatives, nearly half were granted suspension of execution of sentence. Of four elderly homicide offenders who were sentenced to life imprisonment, three had committed homicide at the scene of a robbery (consummated) and one was a Boryokudan leader who had the highest number of previous convictions among elderly homicide offenders. The sentences of those who had committed homicide against relatives tend to be more severe among non-elderly homicide offenders than elderly homicide offenders. Fig. 7-3-2-51 Percent distribution of homicide offenders by sentencing (5) ConclusionAmong elderly homicide offenders, the percent ratio of those who had committed homicide against relatives was slightly higher and many of those who had committed homicide against relatives had no previous conviction/disposition. Many elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives had previous convictions. A breakdown reveals that many had committed offenses since young, but had not continuously repeated offenses with many of them having committed offenses for the first time in decades. In general, their criminal tendencies were not high. Among elderly homicide offenders against relatives, there were cases in which the offender had been living a life without any relation to crime but had become elderly and financially hard pressed due to a reduced income or large sums of debt, or his/own or family members physical disorder, etc., their uncertainty and exhaustion then grew, and they finally decided to seek relief by eliminating those who had been a burden to them (case [1]), in which the offender was discouraged about the future and attempted a forced double suicide (case [2]), and in which the offender started having more time to spend with their family after retiring but could not develop a good relationship with them and the unbearable feeling caused them to explode in anger (case [3]). In addition, although most of them had association with non-relatives, 40% of them were “having troublesome problems”. They could not talk to others about their difficulties and uncertainty and were worried all alone. The consummation rate of those who had committed homicide against relatives was higher than that of those against non-relatives among both elderly homicide offenders and non-elderly homicide offenders. Most elderly homicide offenders against relatives were “not drinking alcohol” at the time of the offenses, indicating that many of those cases were not accidental but a result of elaboration after feeling distressed. On the other hand, among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, many committed offenses as a result of being financially hard pressed or trouble with those they had associated with, when compared to non-elderly homicide offenders. In addition, some cases were caused by their pride, characteristic of elderly (case [4]), but few cases were related to uncertain health, even though the percent ratio of those with diseases was about the same as that among elderly homicide offenders against relatives. Some elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives had a large number of previous convictions and many of them were living unstable lives when compared to those with a small number of previous convictions (case [5]). Among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives who had committed homicide at the scene of a robbery, none had “anger/rage” as the motive/cause nor were drinking alcohol at the time of the offense, indicating that many were planned offenses. On the other hand, among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives excluding homicide at the scene of a robbery cases, over 80% included “anger/rage” as the motive/cause, with the majority being under the effect of alcohol at the time. Many of these characteristics were similar to injury/assault offenders (see sub-section 3 in this section). Among elderly homicide offenders against non-relatives, however, the percent ratio of victims being “strangers” was low while the percent ratio of those having “revenge/grudge” as the motive/cause was high. Hence these cases were not as accidental or unexpected as the injury/assault cases and many resulted from long held discontent and anger against victims exploding. |