| Previous Next Index Image Index Year Selection | |

|

|

5 Background factors behind the increase in heinous offenses committed by juveniles It has been revealed that the number of robbery offenses committed by young people, and in particular by juveniles, has been increasing rapidly. Behind the occurrence of an offense, there is a complex combination of various factors including the offender's personal predisposition, level of consciousness of norms, and family/educational circumstances, as well as social environment at the time of the offense. Although it is difficult to unequivocally clarify the causes of the occurrence of the offense, some clues would be obtained by examining background circumstances. Among the various factors, this subsection will examine the 4 most important ones, which are as follows: (1) decline in parents' guiding ability; (2) difficulty in finding jobs due to recession; (3) changes in attitudes of juvenile delinquents and ordinary juveniles; (4) changes in circumstances surrounding juveniles.

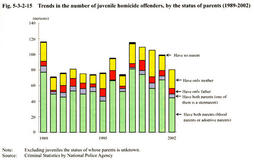

(1) Decline in parents' guiding ability Fig. 5-3-2-15 and Fig. 5-3-2-16 show the trends in the number of juvenile homicide and robbery offenders since 1989, by the status of the juvenile's parents.

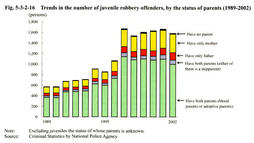

Among homicide offenders, juveniles who have both parents have always accounted for more than 60% and the percentage of those who have only one parent has been below 40%. The fluctuation in the percent distribution has not shown any particular tendency. Among robbery offenders, the number of cleared juveniles who have both parents has been on the rise but the percentage of such juveniles has always been about 70%, without showing much fluctuation. Among juveniles who have committed heinous offenses such as homicide and robbery, the number and the percentage of those who have both parents have been large, and the number of such juveniles has been increasing gradually among juveniles who have committed robbery. These facts indicate the decline in the ability of families, and in particular their parents, to control their children (for details, see Chapter 4, Section 2, 3 ). Fig. 5-3-2-15 Trends in the number of juvenile homicide offenders, by the status of parents (1989-2002) Fig. 5-3-2-16 Trends in the number of juvenile robbery offenders, by the status of parents (1989-2002) (2) Difficulty in finding jobs due to recession Fig. 5-3-2-10 and Fig. 5-3-2-13 in Subsection 4 above indicate an upward trend in the number of unemployed juveniles cleared for robbery, which is due to the increase in the number of unemployed juveniles.

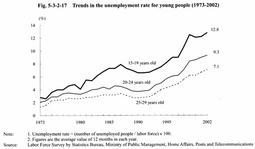

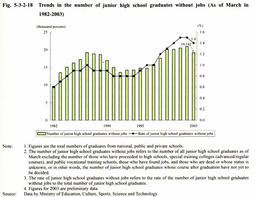

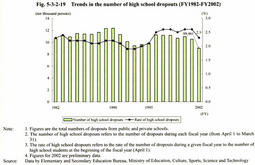

Fig. 5-3-2-17 shows the trends since 1973 in the unemployment rate for young people aged from 15 to 29. The unemployment rate has been rising rapidly for all age groups; among others, the rate for teenagers has surpassed 10% since 1998, which indicates that it is becoming more difficult for teenagers to find jobs due to the recession. As clearly shown in Fig. 5-3-2-18 and Fig. 5-3-2-19 , the numbers and percentages of junior high school graduates without jobs and of high school dropouts remain at a high level that cannot be disregarded, though some favorable signs have been seen recently. Thus, the existence of such a large number of unemployed juveniles who cannot find their places in society may be one of the reasons for the increase in the number of unemployed juveniles who have committed robbery. Fig. 5-3-2-17 Trends in the unemployment rate for young people (1973-2002) Fig. 5-3-2-18 Trends in the number of junior high school graduates without jobs (As of March in 1982-2003) Fig. 5-3-2-19 Trends in the number of high school dropouts (FY1982-FY2002) (3) Changes in attitudes of juvenile delinquents and ordinary juveniles (a) Changes in attitudes of juvenile delinquents and ordinary juveniles The occurrence of an offense committed by a juvenile seems to result not only from the juvenile's family/educational circumstances and social environment including employment situation, but also from the juvenile's motivation for learning, character, and consciousness, which have been developed in these circumstances and environment.

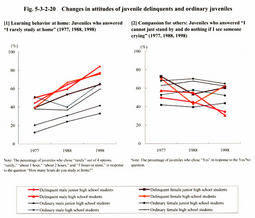

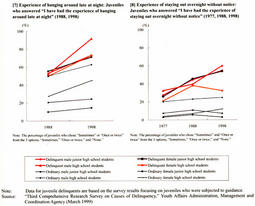

Fig. 5-3-2-20 shows part of the results of the surveys conducted in 1977, 1988, and 1998 regarding the attitudes of ordinary juveniles and juvenile delinquents (who were subjected to guidance by the police), with respect to the questions about juveniles' learning behavior, compassion for others, egocentrism, feeling of fatigue, trend consciousness, feeling toward parents, experience of hanging around late at night, and experience of staying out overnight without notice. Careful consideration is required because these surveys were not conducted focusing on heinous offenses, but they are useful to comprehend the trends over about 20 years in various attitudes that seem to be shared among juvenile delinquents in general. With respect to learning behavior, the rate of juvenile delinquents who answered "I rarely study at home" has been rising sharply. In 1998, the rates exceeded 75% among male junior high school students, male high school students, and female high school students and 60% among female junior high school students, increasing by more than 25 points from 1977 in all these groups. This trend is not specific to juvenile delinquents because the rate of juveniles who rarely study at home has also been rising among ordinary junior high school/high school students. There is a concern over the decline in intellectual level among junior high school/high school students due to decreasing motivation for learning. With respect to compassion for others, the rate of juvenile delinquents who answered "I cannot just stand by and do nothing if I see someone crying" has been declining only among male junior high school students and male high school students. In particular, the rate declined by 27 points in about 20 years from 57.4% to 30.5% among male high school students, which implies that more male high school students are lacking compassion for others. On the other hand, the egocentric tendency such as "I will do what I want to do even if my parents are opposed to it" has intensified among juveniles in general, and the rate of juveniles who agreed with this opinion has increased by 19-31 points in about 20 years among juvenile delinquents. There is no problem if what they want to do is something other than crimes, but we cannot rule out the possibility that juveniles with some criminal tendencies would go ahead and commit crimes. On the other hand, the rate of juveniles who answered "I always feel tired" has been rising constantly among both juvenile delinquents and ordinary juveniles, increasing by about 30 points in about 20 years and surpassing the 50% mark. This implies that more juveniles are losing vitality, succumbing to a feeling of ennui, and feeling depressed in recent years. The rate of juveniles who answered "I am conscious of fashionable clothes and hairstyles" has been higher among juvenile delinquents than among ordinary juveniles, suggesting that juvenile delinquents are more easily affected by fashion trends. With respect to the feeling toward parents, the rate of juveniles who feel "I am not loved by my parents" has been clearly higher among juvenile delinquents than among ordinary juveniles and the rate has been on the rise. In particular, the rate of male juveniles who have such feeling has increased by 23-24 points over about 20 years, indicating that more male juveniles feel a need for the love of their parents. The rates of juveniles who have had the experience of hanging around late at night and of those who have had the experience of staying out overnight without notice have been increasing generally among juvenile delinquents, and particularly among male high school students. The rates of those who have had the experience of hanging around late at night and those who have had the experience of staying out overnight without notice have increased significantly by 39.6 points over about 10 years and by 27.5 points over about 20 years. This indicates an outstanding decline in parents' guiding ability. These survey results suggest that factors that would easily lead to the commitment of crimes, such as decline in motivation for learning and intellectual level, spreading of lack of compassion for others, intensified egocentrism, expanding of the feeling of fatigue, diffusion of the tendency of being easily affected by fashion trends, increase in dissatisfaction towards parents, and a proliferation of experiences of hanging around late at night and of staying out overnight without notice, are further intensifying among Juvenile delinquents. Such changes in attitudes of juveniles are causing the increase in offenses committed by juveniles in general, and in particular the heinous offenses committed by them. Fig. 5-3-2-20 Changes in attitudes of juvenile delinquents and ordinary juveniles (b) Juveniles' views about violence What views about violence are seen recently among juvenile delinquents who have committed violent offenses? Fig. 5-3-2-21 shows part of the results of the survey conducted in 1999 regarding the difference in views about violence between violent juvenile delinquents who were in juvenile classification homes (who had ever been subjected to guidance by the police for heinous or violent offenses), juveniles who had other delinquent records, and ordinary junior high school/high school students. The rate of juveniles who agreed with the view that "Those who suffer violence have done something that provoke the perpetrators to anger" was higher among violent juvenile delinquents of both genders. In particular, among male juveniles, the difference between violent juvenile delinquents and ordinary junior high school/high school students was small, and the rate of those who agreed with this view exceeded 50% in all groups, which indicates the intensified tendency of justifying violence among male juveniles in general. The rate of juveniles who agreed with the view that "Current society has a mechanism in which the strong suppress the weak, and therefore it is impossible to eliminate bullying" was rather higher among ordinary junior high school/high school students than among violent juvenile delinquents, and it exceeded almost 50% in all groups, implying the spreading of resignation that allows or tolerates violence among juveniles in general. The rate of juveniles who agreed with the view that "It is natural to participate in a fight to get revenge for my friends" was particularly high among violent juvenile delinquents, exceeding 60%, which indicates an intensified affirmative tendency towards violence among them.

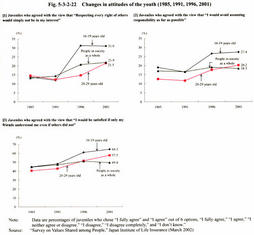

Violent juvenile delinquents indeed have a stronger tendency to justify and affirm violence than ordinary juveniles, but the rate of ordinary juveniles who show such tendency is not low at all. This leads to a concern over the potential danger that a considerable number of ordinary juveniles might involve themselves in violent offenses depending on the circumstances. The spreading of these views about violence among juveniles may have some influence on the increase in heinous offenses committed by juveniles. Fig. 5-3-2-21 Juveniles' views about violence (c) Changes in attitudes of young people and society as a whole Is there any notable change in the attitudes of young people who have more contact with juveniles and of people in society as a whole? Fig. 5-3-2-22 shows the notable results of the surveys conducted by a private research institute, the Japan Institute of Life Insurance, over 15 years (in 1985, 1991, 1996, and 2001), regarding changes in attitudes among juveniles (aged 16 to 19), young people (aged 20 to 29), and people in the society as a whole (aged 16 to 69). Among juveniles, the rate of those who agreed with the views that "Respecting every right of others would simply not be in my interest," "I would avoid assuming responsibility as far as possible," and "I would be satisfied if only my friends understood me even if others did not" increased from 1991 to 1996 by 19.3 points, 10.1 points, and 12.8 points respectively. Such an increasing trend was also seen among young people during the same period, in varying degrees, unlike the trends among people in the society as a whole. This implies that more juveniles and young people have become selfish, irresponsible, and self-righteous. These changes in the attitudes of juveniles and young people do not immediately lead to the commitment of offenses, but they might have a slight impact on qualitative changes in offenses.

Fig. 5-3-2-22 Changes in attitudes of the youth (1985, 1991, 1996, 2001) (4) Changes in environments surrounding juveniles As juveniles are mentally immature, they are apt to respond sensitively to the trends of the times. The fact that more people including juveniles have come to use overnight restaurants and 24-hour convenience stores late at night in addition to game centers and karaoke rooms may be one of the causes of the increase in the number of robbery cases committed by juveniles on the street late at night.

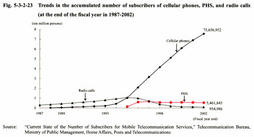

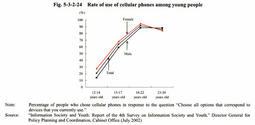

As shown in Fig. 5-3-2-23 and Fig. 5-3-2-24 , the use of cellular phones has been spreading rapidly in recent years. This has made communication between people in dispersed locations very easy in daily life but, at the same time, it has made it infinitely easier for groups of juvenile delinquents to gather or disperse, which might have an influence on the increase in the accomplice rate. Fig. 5-3-2-23 Trends in the accumulated number of subscribers of cellular phones, PHS, and radio calls (at the end of the fiscal year in 1987-2002) Fig. 5-3-2-24 Rate of use of cellular phones among young people |