Section 1 Involvement of Victims in Criminal Proceedings

1 Appeal system against non-prosecution

The power to prosecute is in principle exclusively granted to public prosecutors with rather broad discretion upon prosecution. However, even a public prosecutor can misjudge a case and decide not to prosecute a suspect who actually should have been prosecuted. For this reason a system to appeal against the disposition of a non-prosecution by a public prosecutor was established: a request for the case to be reviewed by a Committee for Inquest of Prosecution and an application for the case to be committed to a competent district court for trial (also referred to as the “quasi-prosecution procedure”).

(1) Request for review by Committee for Inquest of Prosecution

There are currently 165 Committees for Inquest of Prosecution nationwide, and each committee consists of 11 members chosen by a lottery from those listed on the electoral register who serve for six months. Upon receiving a request or ex officio the Committee reviews non-prosecution disposition made by a public prosecutor and then judge whether the case is “appropriate for prosecution,” “inappropriate for non-prosecution,” or “appropriate for non-prosecution.”

Conventionally decisions made by Committees for Inquest of Prosecution have had no legal binding force, with public prosecutors themselves making the final decision on whether prosecution will take place or not after taking into account the decision of the pertinent Committee. The Act on Committee for Inquest of Prosecution (Act No. 147 of 1948) amended by the Act for Partial Amendment of the Code of Criminal Procedure, etc. (Act No. 62 of 2004), however, introduced a system where prosecutions could be instituted based on a decision made by a Committee for Inquest of Prosecution under certain conditions. Within this system, which came into force on May 21, 2009, if a public prosecutor had not prosecuted a case but a Committee for Inquest of Prosecution decided that the case should have been prosecuted and subsequently a public prosecutor decided not to prosecute the case again or did not prosecute the case within a certain period of time, the Committee for Inquest of Prosecution is then required to re-examine the case. If that then results in the Committee deciding that “the case should be prosecuted” (prosecution decision), the court designates a lawyer (designated lawyer) to prosecute the case, and the designated lawyer conducts the duties of public prosecutor in the case pertaining to that decision.

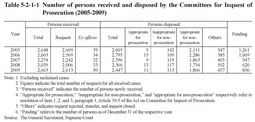

Table 5-2-1-1 shows the number of persons received and disposed by Committees for Inquest of Prosecution (not including reclaimed cases) over the last five years. 2,456 of those received in 2009 were for penal code offenses. By type of offense abuse of authority was the largest in number at 442, followed by counterfeit of documents at 266, negligence in vehicle driving causing death or injury at 264, injury at 226, theft at 194, and negligence in the pursuit of social activities causing death or injury at 192. 207 persons were received for special act offenses, with Labor Standards Act violations being the largest in number at 47 persons (Source: The General Secretariat, Supreme Court).

Table 5-2-1-1 Number of persons received and disposed by the Committees for Inquest of Prosecution (2005-2009)

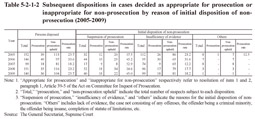

Table 5-2-1-2 shows the subsequent dispositions by public prosecutors in cases decided as appropriate for prosecution or inappropriate for non-prosecution by reason of initial disposition of non-prosecution over the last five years.

The number of cases decided as appropriate for prosecution by the Committee but their non-prosecution was upheld by public prosecutors and then re-examined by the Committee was one in 2009, and for this case, the Committee didn't reach the prosecution decision. Up to the end of July 2010 the number of cases for which a prosecution decision took place was five (Source: The General Secretariat, Supreme Court).

Table 5-2-1-2 Subsequent dispositions in cases decided as appropriate for prosecution or inappropriate for non-prosecution by reason of initial disposition of nonprosecution (2005-2009)

From 1949 (after enforcement of the Act on Committee for Inquest of Prosecution) to 2009 a total of 155,583 persons were disposed by the Committees for Inquest of Prosecution, with 17,444 (11.2%) decided as appropriate for prosecution or inappropriate for non-prosecution. 1,444 were then prosecuted, 1,286 convicted (447 sentenced to imprisonment and 839 to fine) and 81 found not guilty (including Menso adjudication and dismissal of prosecution) (Source: The General Secretariat, Supreme Court).

(2) Application for committing cases to a court for trial

The application for committing a case to a court for trial is a system that enables anyone that has filed a criminal complaint or accusation for an offense committed by public officials, including abuse of authority, etc., to then apply to a competent district court for committing the case for trial if they are dissatisfied with a public prosecutor's non-prosecution disposition. The district court then renders the ruling that the case should go to trial if the request is well-grounded. As a result of that ruling, prosecution of the case is deemed to have been instituted and the court then designates a lawyer to sustain the prosecution (a “designated lawyer”), with the designated lawyer then conducting the duties of the public prosecutor for the case.

In 2009 the number of persons newly received via applications to commit the case to a court for trial was 353 and the number of persons disposed 425. The decision to commit the cases to a court for trial was made for two persons (Source: Annual Report of Judicial Statistics and The General Secretariat, Supreme Court).

Between 1999 and 2008 a total of 2,826 persons were disposed and the decision to commit the case to a court for trial was made for one person. From 1949 (after enforcement of the current Code of Criminal Procedure) to 2009, the number of persons for whom the cases were decided to be committed to a court for trial, deemed to be prosecuted and judgment became final was 18. Nine of them were convicted (eight sentenced to imprisonment and one to fine) and nine found not guilty (including Menso adjudications).