| Previous Next Index Image Index Year Selection | |

|

|

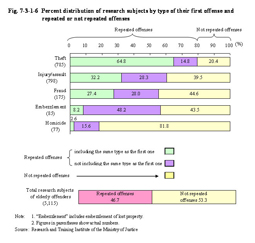

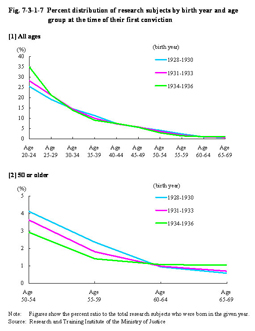

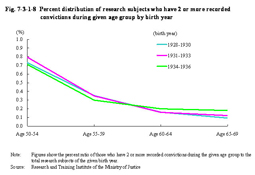

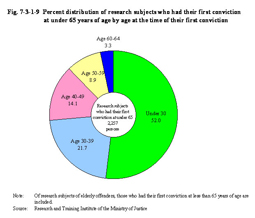

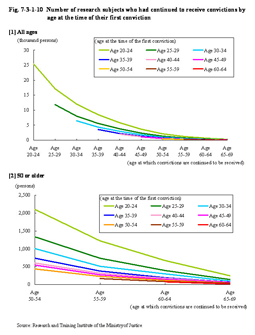

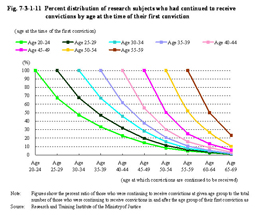

4 Characteristics of offenses by elderly offenders Fig. 7-3-1-5 Percent distribution of research subjects by age at the time of conviction and type of their first offense Of 53 elderly repeat offenders whose first offense was theft, 92.5% (49 persons) of their second offenses were theft. Of those who committed a third offense (10 persons), all of their offenses were theft. As revealed above elderly offenders who have committed theft tend to repeat theft. The background and causes, etc. of this will be discussed in Section 2 of this chapter.Finally, the research subjects of elderly offenders' tendency to repeat offenses by type of their first offense reveals that those who had committed theft as their first offense have the highest tendency to commit offenses of the same type (64.8%), followed by those who had committed injury/assault and fraud as their first offense (see Fig. 7-3-1-6). Overall, nearly half of them repeated offenses. The tendency to repeat offenses of the same type by age using the recorded convictions was shown above (see 3 of this section). Here the tendency to repeat offenses of the same type is discussed by type of offense. Of the research subjects of elderly offenders (5,115 persons), theft and injury/assault were the highest in actual number and tendency to repeat the same type of offense. For those whose first offenses were theft and committed another type of offense at least once (625 persons), 29.4% (184 persons) committed theft in all their repeated offenses while 52.0% (325 persons) repeated theft at least once, which confirms the high tendency to repeat theft. For those whose first offenses were injury/assault and committed another offense at least once (483 persons), 15.1% (73 persons) committed theft in all their repeated offenses while 38.1% (184 persons) repeated theft at least once. Although not as high as theft, more than the majority repeated the same type of offenses. Fig. 7-3-1-6 Percent distribution of research subjects by type of their first offense and repeated or not repeated offenses Reference: Relationship between Age and Criminal TendenciesUnderstanding the relationship between age and criminal tendencies is important in enabling effective measures to be mapped out by targeting certain age groups for focused offense prevention. Past studies have revealed that, regardless of country or region, the offense rate per population by age (for example number of persons cleared for non-traffic penal code offenses per 100,000 persons of the same age) starts to increase in early adolescence (around 13 years old), reaches a peak around mid-adolescence (16–17 years old), and then turns to a decreasing trend. This then means that the number of persons newly committing offenses decreases and that those who have committed offenses also stop repeating offenses as they age. The following 2 cases will discussed in examining whether general trends in the offense rate per population by age matches the trends of research subjects in Japan or not. The first case is whether the rate of research subjects who committed their first offense at an elderly age decreases as they further age or not. The second case is whether those with histories of offenses before reaching an elderly age are less likely to repeat offenses (stop committing offenses) as they age or not. According to general trends in the offense rate per population by age both the two cases should have decreasing trends. With the first case, the age of research subjects at the time of their first conviction shows that [1] for those born in 1928 to 1933, the rate of persons who had their first conviction decreases with the advancement of their age, matching the above mentioned general trends in the relationship between age and criminal tendencies. However, [2] those born in 1934 to 1936 have a somewhat different trend in that [1] the rate of persons who had their first conviction decrease with the advancement of age but quite gently after 60–64 years of age (see Fig. 7-3-1-7). Fig. 7-3-1-7 Percent distribution of research subjects by birth year and age group at the time of their first conviction With the second case, the tendency to repeat offenses by age group (see Fig. 7-3-1-8) shows that [1] for those born in 1928 to 1933, the rate of persons who repeat offenses decreases as they age, matching the above mentioned general trends in the relationship between age and criminal tendencies. However, [2] for those born in 1934 to 1936, the decrease in rate of persons with two or more recorded convictions (repeat offenders) at age 50 or older slows down after reaching 60–64 years of age, which then means that some of those in [2] did not stop committing offenses around 1999 and 2001. There are only a small number of such offenders, no more than 1%, but it did reveal that some of them go against the general trend where people stop repeating offenses as they age.Fig. 7-3-1-8 Percent distribution of research subjects who have 2 or more recorded convictions during given age group by birth year With those who did not stop committing offenses at an elderly age, the age at which they had their first conviction (see Fig. 7-3-1-9) shows that about half of them had their first conviction at under 30.Fig. 7-3-1-9 Percent distribution of research subjects who had their first conviction at under 65 years of age by age at the time of their first conviction Fig. 7-3-1-10 shows the number of persons who had repeated offenses by the age group at which they had their first conviction. Among those who continued to commit offenses at age 65 or older, many had their first conviction in their early 20s. Adding the figure for late 20s to that of early 20s, in total, revealed about 50% had their first conviction while youths (see Fig. 7-3-1-10 [2]).Fig. 7-3-1-10 Number of research subjects who had continued to receive convictions by age at the time of their first conviction Next, the rate of persons who had continued receiving convictions (hereinafter referred to as the “repeat offense continuation rate” in this sub-section) by age group at which they had their first conviction was used to analyze the situation. The repeat offense continuation rate was calculated for each age group at which persons had their first conviction by dividing the number of those in the age group who had not stopped repeating offenses at a particular age (on and after the first conviction) by the total number of the age group, which revealed that the repeat offense continuation rate decreases most gently for those who had their first conviction in their early 20s (see Fig. 7-3-1-11). Comparing the repeat offense continuation rate 10 years after the first conviction resulted in 47.3% for the age group of early 20s, 45.8% for early 30s, 30.0% for early 40s, and 26.7% for early 50s.Fig. 7-3-1-11 Percent distribution of research subjects who had continued to receive convictions by age at the time of their first conviction The meaning of that decrease will now be described in more detail. For instance, among those who had their first conviction in their late 40s, about 25% continued receiving convictions 10 years later in their late 50s. On the other hand, among those who had their first conviction in their early 20s, only 5% continued receiving convictions into their late 50s. Upon comparing the two groups the former would seem to be more problematic. However, among those who had their first conviction in their late 40s, the number of those who continued receiving convictions decreases rapidly to about 1/4 over 10 years. And among those who had their first conviction in their early 20s, 47.3% continued receiving convictions 10 years later into their early 30s, making it obvious that the rates of decrease for the groups differ with regard to the repeat offense continuation rate over the same period. In addition, among those who had their first conviction in their 20s, only about 1% continued receiving convictions up to an elderly age of between 65 and 69. However, since the number of persons who had their first conviction in their 20s is large when compared to those who had their first conviction in their 30s or older, despite the small percent ratio, the actual number of such elderly offenders is significantly large (see Fig. 7-3-1-10).As described above, not simply because they were young and could commit offenses over a long period of time, it was revealed that this age group shows high criminal tendency with recorded convictions even at younger stages of their lives. Therefore, developing measures to prevent young offenders from repeating offenses could be part of preventive measures against elderly offenders. As given in Fig. 7-3-1-11, although the repeat offense continuation rate for late middle age group (50 or older) declines more rapidly over time (to about 1/4 over 10 years) than that for younger groups, there are some in that group who had obviously been repeating offenses. Although the actual number of such offenders is small (see Fig. 7-3-1-10), for those who had their first conviction in their late middle age and have a strong tendency to repeat offenses, research on causes for repeating offenses through further analysis on the type of offenses and their attributes/environment will be necessary in the future in designing effective measures. |