2 Economic offenses

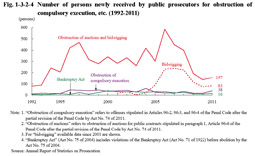

Fig. 1-3-2-4 shows the number of persons newly received by public prosecutors for obstruction of compulsory execution (refers to offenses stipulated in Articles 96-2, 96-3, and 96-4 of the Penal Code after the partial revision of the Penal Code by Act No. 74 of 2011; hereinafter the same in this subsection), obstruction of auctions and bid-rigging (refers to obstruction of auctions for public contracts stipulated in paragraph 1, Article 96-6 and bid-rigging stipulated in paragraph 2, Article 96-6 of the Penal Code after the partial revision of the Penal Code by Act No. 74 of 2011; hereinafter the same in this subsection), and violations of the Bankruptcy Act (Act No. 75 of 2004; Act No. 71 of 1922 before its abolition by the Act No. 75 of 2004 in December 2004) over the last 20 years. The number of persons received for obstruction of auctions and bid-rigging sharply increased from 1994 through to 1997, and then remained at a high level. However, it significantly decreased from 2009. In 2011 it increased by13.8% from the previous year to 157.

Fig. 1-3-2-4 Number of persons newly received by public prosecutors for obstruction of compulsory execution, etc. (1992-2011)

Table 1-3-2-5 shows the number of persons prosecuted or not prosecuted for obstruction of compulsory execution, obstruction of auctions, bid-rigging, and Bankruptcy Act violations over the last five years.

Examining the details of prosecutions in 2011 revealed that four persons for obstruction of compulsory execution, eight for obstruction of auctions, and three for bid-rigging were requested summary order while all the others were indicted (Source: Annual Report of Statistics on Prosecution).

The partial revision of the Penal Code in June 2011 (by Act No. 74 of 2011) expanded the acts subject to a penalty and raised the upper limit of the statutory penalty for obstruction of compulsory execution, etc. (enforced on July 14, 2011).

Table 1-3-2-5 Number of persons prosecuted or not prosecuted for obstruction of compulsory execution, etc. (2007-2011)

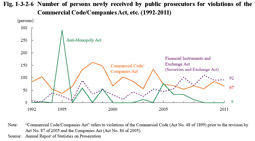

Fig. 1-3-2-6 shows the number of persons newly received by public prosecutors for violations of the Commercial Code (Act No. 48 of 1899 prior to revision by Act No. 87 of 2005)/Companies Act (Act No. 86 of 2005; enforced on May 1, 2006), the Anti-Monopoly Act, and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (Act No. 25 of 1948; the title of the act was “Securities and Exchange Act” prior to September 30, 2007) over the last 20 years.

Fig. 1-3-2-6 Number of persons newly received by public prosecutors for violations of the Commercial Code/Companies Act, etc. (1992-2011)

In FY 2011 the Securities and Exchange Surveillance Commission filed formal accusations regarding Financial Instruments and Exchange Act violations against 46 persons (including juridical persons) in 15 cases. By type of violation, 11 of them in six cases were accused for “insider trading,” 18 persons in four cases for “submission of annual securities reports, etc., containing false statements,” 16 persons in four cases for “spreading rumors, using fraudulent means, and committing assault or intimidation,” and one person in one case for “market manipulation” (Source: The Securities and Exchange Surveillance Commission). The Japan Fair Trade Commission filed no accusations for Anti-Monopoly Act violations (Source: The Japan Fair Trade Commission).

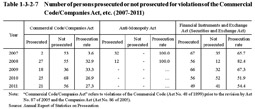

Table 1-3-2-7 shows the number of persons prosecuted or not prosecuted for violations of the Commercial Code/Companies Act, the Anti-Monopoly Act, and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (Securities and Exchange Act) over the last five years.

Examining the details of prosecutions in 2011 revealed that two persons for Companies Act violations and three persons for Financial Instruments and Exchange Act violations were requested summary order while all the others were indicted (Source: Annual Report of Statistics on Prosecution).

Table 1-3-2-7 Number of persons prosecuted or not prosecuted for violations of the Commercial Code/Companies Act, etc. (2007-2011)

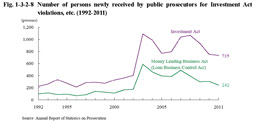

Fig. 1-3-2-8 shows the number of persons newly received by public prosecutors for violations of the Investment Act and the Money Lending Business Act (Act No. 32 of 1983; the title of the act was “Act on Regulation, etc. of Loan Business” (hereinafter referred to as the “Loan Business Control Act”) prior to December 19, 2007) over the last 20 years. The number of persons received for violations of either of these acts sharply increased in 2003 and then remained at a high level. In 2011 the number of persons received for Investment Act violations was 735 (down 2.5% from the previous year) and that for Money Lending Business Act violations 242 (down 20.1% (id.)).

Fig. 1-3-2-8 Number of persons newly received by public prosecutors for Investment Act violations, etc. (1992-2011)

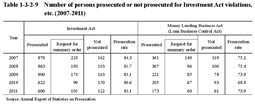

Table 1-3-2-9 shows the number of persons prosecuted or not prosecuted for violations of these acts over the last five years.

Table 1-3-2-9 Number of persons prosecuted or not prosecuted for Investment Act violations, etc. (2007-2011)

The Money Lending Business Act and Investment Act were revised by Act No. 115 of 2006 to counteract black-market financing. The upper limit of the statutory penalty for non-registered business activities was raised from imprisonment with work for 5 years to that of 10 years (enforced on January 20, 2007) and a new penal provision of imprisonment with work for 10 years as the upper limit of the statutory penalty was set for loan businesses imposing a higher interest rate than 109.5% per year (enforced the same day). In addition, the revision lowered the interest rate to which the penal provision for a high-interest loan business is applied (the upper limit of the statutory penalty is imprisonment with work for five years) from more than 29.2% per year to more than 20% per year (enforced on June 18, 2010).